Stephen King sets out his stall early in Later: “Like I said,” narrator Jamie Conklin tells us, “this is a horror story.” Jamie is a normal boy growing up in New York, the son of Tia, a single mother and literary agent who tells him pleasingly self-referential things such as “most writers are as weird as turds that glow in the dark”. Olivia, Ted’s cat, given wonderfully vain voice by Ward, imagines them “all screaming in the dark, unable to move or speak”, as the outer sits “broad and blankly smiling”.

Ward has created something exceptionally unsettling here, as many-layered and sinister as the Russian doll that sits on Ted’s mantelpiece. She “feels like a big, dark, empty room” and is fixed on finding whoever took Lulu. Dee’s family and life have fallen apart after the disappearance of her sister Lulu. Ted lives in a boarded-up house on Needless Street on the edge of the forest, with his daughter Lauren (who sometimes has to go away) and his cat Olivia he is confused, childlike, flipping in and out of the present and the past as he remembers being questioned by the police years earlier over the disappearance of “Little Girl With Popsicle”, and as he thinks of his mother, who was “born far away… under a dark star”. This is the most gloriously complex, shifting story, deeply disturbing yet also, somehow, heartwarming. That might make The Last House on Needless Street sound straightforward – it’s not.

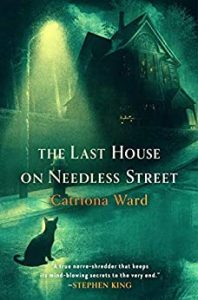

It is the story of a child whose life was stolen, of Ted, the man who may or may not have done it, and of Dee, the sister out for revenge. Catriona Ward’s The Last House on Needless Street, which opens 11 years after a little girl vanishes on a family trip to a lake, comes emblazoned with glowing – and much-deserved – praise from her fellow authors: Stephen King, no less, calls it the most exciting novel since Gone Girl, and “a true nerve-shredder”.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)